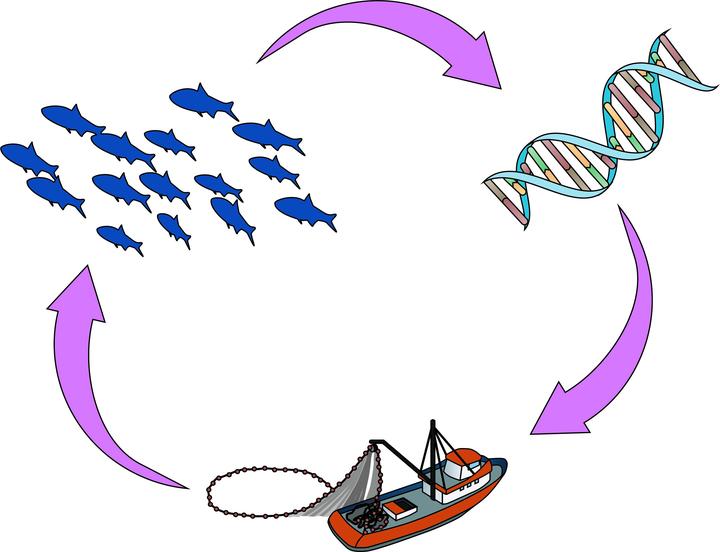

Filling the communication gap between genomics and marine fisheries

vector images downloaded from Integration and Application Network (University of Maryland)

vector images downloaded from Integration and Application Network (University of Maryland)Next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have opened a bast array of possibilities for research in the different fields of biological sciences. At this point a rather too optimistic (or actually quite pessimistic) soul would think that there is little left to discover in terms of the complexity written in DNA molecules. It turns out however that we may have not even started to unravel all that complexity. This was stated not long ago by Dr. Harris Lewin on his talk at Frontiers Forum (see the talk here). It is also clear when following scientific literature and finding out that the best genomes (most complete) have only just been assembled (latest publication from the Vetebrate Genomes Project). But not only do we observe slow progress in basic science towards understanding non-model organisms, we also find this on its application to conservation and management; and at the edge of an incoming climatic crisis we must not delay.

The issues for integration of genomics in marine fisheries

In marine fisheries, genetic and/or genomic data can provide with relevant information such as the delineation of independent populations, the impact of climate change in marine stocks, the traceability of fisheries products and the impact of fisheries on evolutionary capacity and resilience (Benestan, 2019). In spite of the broad number of themes that genomics can feed, its integration on fisheries management is being slow and patchy. Barriers and limitations were thoroughly identified by Ovenden et al. (2015) for all approaches genomics are useful in marine fisheries. For the most recurrent usage of genetics and genomics into marine fisheries, i.e. defining stock structure, limitations and potential improvement were exposed by Waples et al (2008). A common limitation exposed by these reviews is the lack of communication and reciprocal training among geneticists, fishery biologists and managers. Other fundamental limitations include the lack of reference material for a variety of genetic approaches (highlighted at the very beginning of this post). Still, the lack of reference material and other limitations can be overcome by proper communication among the interested actors. The more fishery biologists and managers are interested into applying genetic methods, the quicker the technology can advance and spread to different species and to different countries. In other words, the faster we get these people interested, the faster we will get good quality genomes.

Survival guide for the fisheries geneticist

Most researchers in genetic related fields are pure academics (with the possible exception of those involved in clinical research), and starting to work out of that environment, with the industry and applied researchers, can be uncomfortable and cumbersome. Here, I intend to describe attitudes and ways for geneticists to successfully integrate their knowledge and research into marine fisheries (although these could also be applied when considering other natural resources). The approaches I talk about are the result of my navigation through the literature and some personal experience:

- Learn to talk the same language. Assuming you and the other stakeholders speak the same human language, you know, the one you use to flirt and conquer other people’s hearts, there is still a language barrier you have to break. These are detailed considerations:

- Translate your own language. I was quite surprised not long ago when two of my peers asked me to define “genome” for a presentation I was about to give for industry directives. The thing is, some of us are so familiar with certain terms we ignore the fact that most people may be completely ignorant about them. Providing 100% correct definitions may not help either- these are usually long and quite technical. Going back to the “genome” example, I could have defined it as the “complete haploid set of chromosomes on a living organism”… You see the questions coming: what is haploid? what is a chromosome? So, simplifying definitions, even on the sin of explaining half the truth, can make others understand in what page you are. If you use these tools well enough, your audience could build up complexity on their own minds and eventually get to the complete image by themselves.

- Create context. You could relate this to your past efforts in learning Korean (I know you are clever): it is much easier to learn language when context is given. Our brains tend to be efficient and lazy, if we do not find much usage to something we may very well forget about it. This can be tackled by creating familiar situations where we need to know the term or how to apply the method we want to inform about. Familiar situations can go all the way from a walk in the park to setting a quota for a specific stock, the difference being that the former is way more common (that is, if you leave your mum’s basement every now and then) and the later is quite specific- to know what is familiar, you should be aware of who is it you are talking with. A failure of this sort is found on teaching mathematics in several disciplines: imagine our horror as biology students when in our VERY first day we attended a mathematics lecture with completely new terminology and no obvious application to the biological questions we were interested to answer.

- Compromise in learning their language. For a geneticist interested in working on marine fisheries, knowing how classical stock assessment is conducted should be fundamental. There are of course issues to this: you need to start basic, you need to find good material to learn by yourself or have someone who explains the new concepts well enough (that person applying considerations 1 and 2). Assessment and management bodies should also consider developing training frameworks when employing non-fishery related scientists and personnel. For your part, you shall have to put your will into it.

From Bernatchez et al. (2017)

Do not believe genetics is the ultimate thing. Between you and me, genomics and genetics are awesome for so many things they should be considered “God’s word” in all biological fields, right? Well, if you are inquisitive (and I am assuming that much), you may start asking, “and what did create God?”, “where can God be found?”, “but if everywhere, did He/She create him/herself?”… just imagine a kid going on and on with questions you do not know how to answer. That is the risk you are taking when taking something as absolute.

- Not all evidence comes from genetics. Do not get me wrong, population genetics and genomics are way more sound and objective than any religion to explain the natural world, as they inherit from the scientific method. Additionally, they stand at the very basis of life complexity. However, and as I said before, we do not have full knowledge of genomic complexity in living beings. In many occasions you may encounter fishery model’s findings that conflict with your genetic findings. Who knows, perhaps that model they make is taking vital information that you are not taking in consideration. It is here when fishery biologists become the questioning kids, trying to find out why your thing is different or whether you are making mistakes. The solution for this is taking a more holistic approach: you are not the God with the ultimate answer, you are part of a team, and the answer tends to lie on a combination of different evidence, that coming from genetics, fisheries, tagging experiments, etc.

- Create or be part of interdisciplinary groups. Pretty much in relation with the last point: in order to make contrasts between different pieces of evidence, and thus reach a sound conclusion on, for instance, the stock structure of hake in the Mediterranean, interdisciplinary research groups should be formed. Imagine for this you are a detective: you go to the crime scene and there is blood but no cadaver nor other reliable information. Grissom however found fly larvae that hatch only in corpses after certain time. After some analyses you determine the time of death, and whose blood that was; then some of your peers find a deer carcass in advanced state of decomposition (with fly larvae all over), on the container, just outside the building where the crime scene is. You start to think that the fly larvae at the crime scene were there not because of the victim but because of the deer, and maybe the victim (or the murderer) was a hunter. Only by unraveling all evidence could you learn that you should not go to that restaurant you liked so much anymore. Determining all relevant aspects for sustainable exploitation of marine fisheries cannot be achieved with just one approach. If Temperance Brennan and Gil Grissom work with other different people to solve crimes, why shouldn’t we to guarantee sustainable exploitation?

Tackle technical limitations. The set of tools you use will most likely have some limitations. Before you apply for a project or start the work, take some time to consider these, then design your study accordingly. Limitations vary from the little trust managers and fishery biologists may have on the method you want to use, to SNP ascertainment bias, to the little use you are going to find for effective population size. Some general recommendations and issues you may find in the literature are:

- For population structure studies, can I sample spawning individuals? Spawning areas are supposed to be representative of a real independent population.

- If allowing for time replication, how much time should there be between sampling?

- Is there good reference material to use? reference genomes or genetic markers?

- How am I going to find outliers, a.k.a non-neutral genetic markers?

- How can I find demographic patterns?

- How much of what I found is due to environmental change? Consider for this the growing field of seascape genomics.

The best you can do is spend some days reading what other authors have come across in their own experience and find reviews about it. Reviews such as that produced by Grünwald et al. (2017) can prove useful.

- Be humorous and close. This is an optional as not all of us have good social skills, and most people working with you should be mature enough to collaborate, even when they do not like you. Indeed, if you ask me, we researchers have already a ton of responsibilities and roles that tend to define single jobs: we are writers, teachers, administrators, empiricists, sellers (no? what about a research proposal? is that not a bit of selling?) and philosophers. So if someone has to tell us apart by how “likable” we are, well… that’s… just… perfect. The capacity to make our job should not be judged by how amiable we are. Nonetheless, being human is a reality: we are not isolated individuals. In an environment working with completely different people to yourself, developing your social skills can enhance reciprocal learning and can ease the resolution of disagreements. Just to make this point clearer, click here to see a wonderful talk by the late Rita Pierson (my point is at the beginning of the talk).